Figure 1 - Al Jazeera

In The Taliban and the Crisis of Afghanistan, M. Nazif Shahrani, a professor of Anthropology, Central Asia, and Middle East studies, describes the Taliban Movement from a historical perspective and considers three essential aspects of Afghanistan’s history that prepared the ground for the rise of the Taliban.

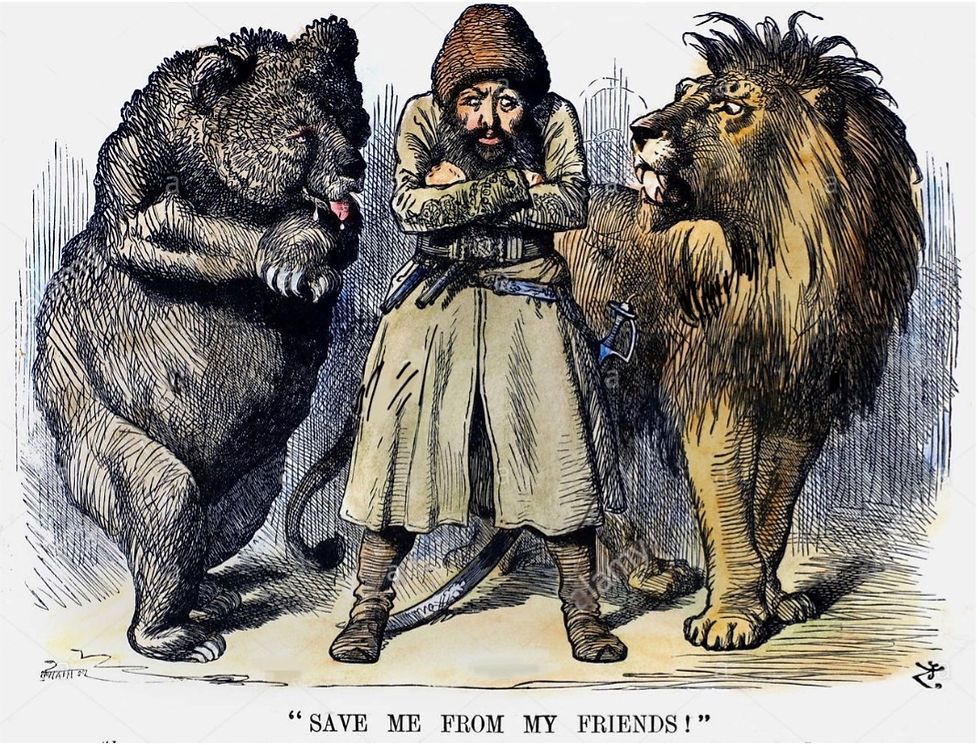

Firstly, the so-called “Great Game” period, starting around 1830, made Afghanistan a venue for political and diplomatic disputes between the British Empire and Tsarist Russia. These two nations competed over the territory of Central and South Asia. Britain was concerned about Russia’s power in the area and fearful of the possible involvement of India in its imperial run. That said, the British Empire wanted to manage the Afghan territory as a protectorate and buffer-state against Russia’s power. Afghanistan was, therefore, entangled in a climate of competition between two powerful empires and a consequent threat of war. Several conflicts emerged from this: the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1838, the First Anglo-Sikh War of 1845, the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1848, and the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878. Moreover, according to Shahrani, Afghanistan was throughout the “Great Game” period “a Pashtun-dominated buffer-state” that received support from western countries, mainly Britain and the Soviets, and was particularly hostile to other ethnic groups living in Afghanistan (Shahrani, “The Taliban,”155). Pashtun is an Islamic ethnic group that predominates in the east and south of Afghanistan, in Pakistan, and within the Taliban movement, while many other ethnic groups coexist in the Afghan territory. This dividing climate is directly connected with the rise of the Taliban movement a century later, whose main intention was to eradicate western’s influence over Afghanistan, restore order and implement sharia law in the whole country.

Figure 2 – Worldie. A caricature depicting Russia’s and Britain’s relations with Afghanistan as a buffer-state.

A second significant aspect to understand the rise of the Taliban movement is the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviets. It led to more war and conflict in the territory – the Soviet-Afghan war – held between the Soviet army supported by the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, and the Afghan mujahedin (meaning ‘one who wages jihad’ and fights against any enemy of Islam). This conflict intensified the instability in the country and created more divisions and antagonism between its people. When the Soviet army finally collapsed in April 1992 and left the territory, civil war continued in Afghanistan, a product of its lasting sectarian disposition. The Taliban constituted one of those sects, which leads us to the third aspect in consideration: the violent climate that emerged in the territory following the dismantlement of the Communist regime and the subsequent rise of mujahedin leadership. There were civil wars all over the country. Shahrani considers the conflicts after 1992 as manifestations of “Pashtun-dominated nation-state building policies shaped by decades of Cold War politics in the region” (Shahrani, “The Taliban,”156). In southern Afghanistan and Kandahar, for instance, there were dozens of small ex-mujaheddin warlords’ groups from different ethnicities who fought against each other: the Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and the Shi’a Hazaras. This internal warfare among mujahedin between 1992 and 1994 led, inevitably, to the rise of the Taliban. These people believed in a fundamental reorganization and restoration of order and sharia law in the Afghan territory. Many of them were born in Pakistan refugee camps, educated in Pakistan madrassas (Islamic schools; Talib means an Islamic student 'who seeks knowledge'). They learned how to fight and were trained for a very specific goal: to implement an ideal Islamic society, built according to the Prophet Mohammed's sayings and teachings.

In such turbulent and violent times, the Taliban were often asked to solve local disputes. The movement’s first supreme leader was Mullah Muhammad Omar, and some of the stories told about him include how his men overthrew conflicts between mujahedin commanders who abused their power. It is said that, in the early stages of the Taliban movement, Omar sent his men to save two girls who were being abused by a commander in Singesar, a village next to Kandahar. Later, his men helped a boy disputed by two commanders in Kandahar who wanted to sexually abuse him. Whether these stories are true or mere myths is hard to tell. However, given all the instability and insecurity prevailing in Afghanistan, it was just a matter of time until the Taliban took Kandahar in 1994, without resistance. One year later, in 1995, the city of Herat fell under their control, also without much fight. In September 1996, the Taliban took control over Kabul and established a Taliban Emirate. Their main goal was clear: the “purification” of Afghan society which, in their view, went completely astray from the Islamic creed, becoming a country of “corrupt, western-oriented time-servers”(Shahrani, “The Taliban,”159). Once in power, the Taliban established a system that strictly followed sharia law, closed girl’s schools, prohibited women from working outside their homes, banned some sports and activities, and forced men to grow long beards. TVs were frown upon and many of them were destroyed.

From 1996 to 2001, the Taliban had power over Afghanistan. In 2001, a coalition of US forces and various Afghan anti-Taliban groups defeated the Taliban regime without much resistance. Nevertheless, the movement never ceased to exist. Its members continued to organise themselves and never gave up on materialising their ideal Islamic society. They persevered in such a way that, twenty years later, the Taliban returned and are, once again, in control of Afghanistan.

Sources:

Shahrani, M. Nazif. “The Taliban and Talibanism in Historical Perspective”, in The Taliban and the Crisis of Afghanistan, ed. Robert Crews and Amin Tarzin (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2009), 155-181.

Ignorar a História semeia violência.

Ignoring History sows violence.

Good Article. Very interesting view